Note: In my last post I incorrectly referred to Demian DinéYahzí’ as Two Spirit. Indigenous Nadleehi Diné is correct.

In the intervening weeks since the first part of this essay was posted, my friend the artist Henk Pander was diagnosed with cancer and died on April 7, 2023. I had been working on a portrait of Henk and wanted to finish it before he died. There will be more on that in a later post. As a result this part of Institution as Thug or Butterfly was delayed. Thanks for your patience.

“How do you know what my best interest is?

How can you say what my best interest is?

What are you trying to say, I'm crazy?

When I went to your schools, I went to your churches

I went to your institutional learning facilities

So how can you say I'm crazy?”

From Institutionalized by Suicidal Tendencies

Lyrics by Mike Muir and Louis Manuel Mayorga

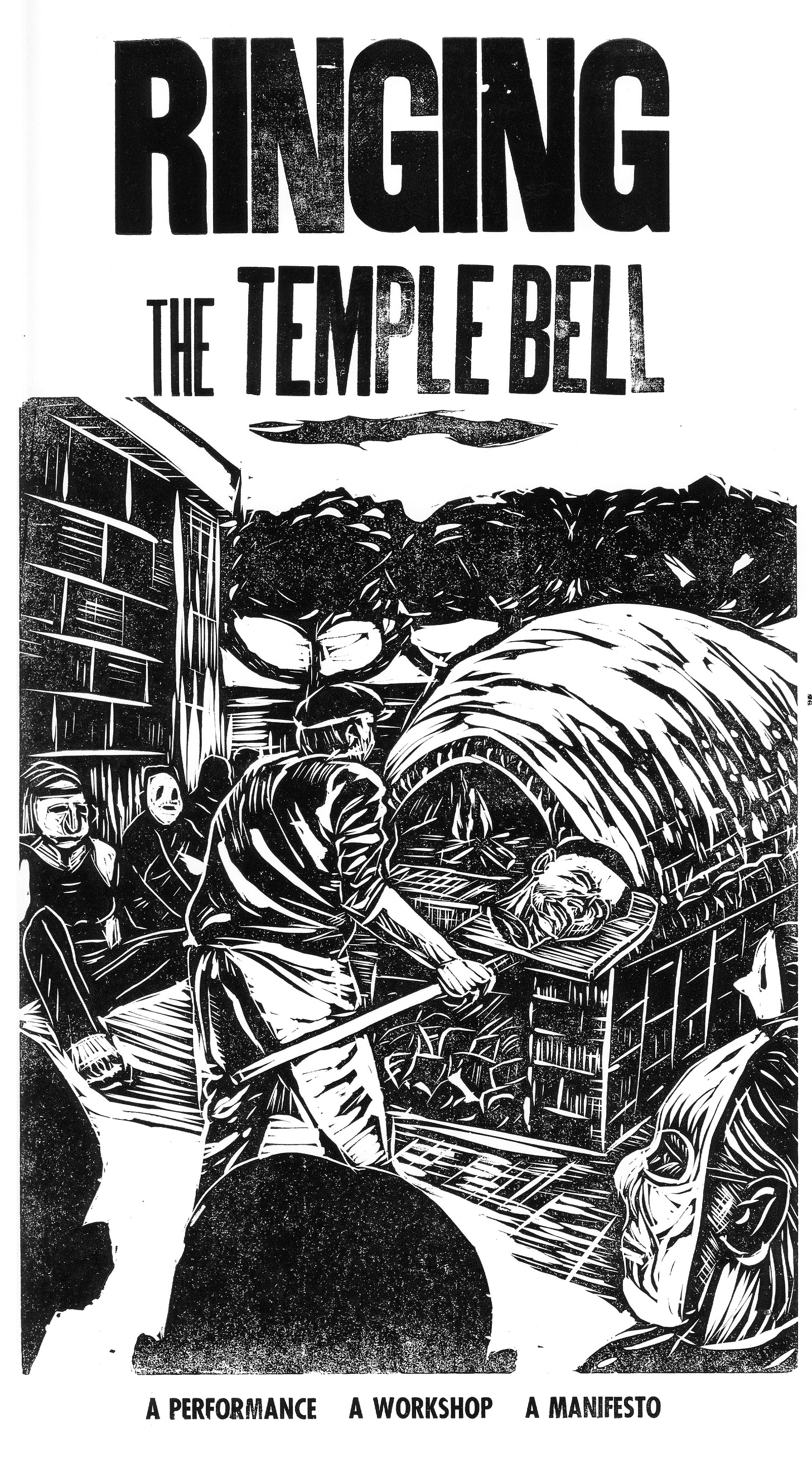

In 2013, after winning an Art Matters award, I presented a piece called Ringing the Temple Bell (a three-day performance/lecture/workshop) at The Queer New York Arts Festival. Building an earthen bread oven in the lower Eastside was the heart of the piece, an act to sacralize making. The ceremonial creation was also meant as a critique of institutions. As winter settled in, I spent three days in the courtyard of the Abrons Art Center building a clay kiln and reading poems to the downtown squirrels and crows. I felt woefully unprepared—and cold. My anti-institutional piece didn’t quite fit into a festival celebrating queerness. I took the experiment and dismantled it for parts. Those parts became seeds and those seeds grew as weedy survivors through the abandoned pavement of my practice. In this moment, I understand how to use them.

Lou Reed died the first day I arrived. I walked along the gray streets from the Bowery feeling impending failure. On my way to Abrons, I thought Lou Reed’s uncompromising approach to life. Over five decades, he coaxed complexity and rage, beauty, tenderness and irritation out of seemingly simple means. I felt the loss personally. During art school in the eighties, The Velvet Underground was my soundtrack. As a working artist I listened to Songs for Drella, Reed and John Cale’s rock opera/homage to Andy Warhol on repeat in my studio. They speak to their mentor about life and art. There is a world hinted at on that album — and I have wanted to belong. “Andy is in the air we breathe,” says Jerry Saltz in the essay “This Too Is Andy Warhol: The Story of an American Revolutionary in Eight Works” from Art is Life. Reed and Cale recount tales of downtown New York with dinners and clubs where artists and gallerists commingle. Every mundanity becomes an occasion for legendary anecdote. This is the air I want to breath. But this Art World might as well be the Otherworld in Celtic mythology. Just beyond a veil, but wholly unreachable.

Andy Warhol seems the poster child for a corrupted, hierarchical, money-obsessed art world. His name graces a foundation that funds current art projects and his oeuvre exemplifies out of reach auction prices. The screen-printed face represents one aspect of the institution—the surface. Songs for Drella scratches below the surface to present a different portrait. In the song “Work,” Warhol’s working-class Catholic roots are his mantra: “He'd probably say you think too much/That’s cause there's work that you don't want to do/It’s work/The most important thing is work.” Artists want the accolades and the market value, but in the end we want them so we can make the work.

In some circles, Warhol’s public image continues to circulate — the distant gadabout, the conman whose work is empty of anything, but monetary value. Saltz says about Mustard Race Riot 1963, “But Warhol was political in other ways. And not only as a swish gay man who openly celebrated queer sex and sexuality. Warhol may have voted only once, but he noticed things and then painted what he noticed. He noticed with a vengeance.” So Andy Warhol and Lou Reed are icons, revered and firmly ensconced in the pantheon. Nevertheless they wriggle against being embalmed by fame. Their work lives. What then, is this Institution I’m so worked up about? What is this Art World I want membership into? It seems to be in exact opposition to the ethos of my Abrons effort.

Those parts became seeds and those seeds grew as weedy survivors through the abandoned pavement of my practice. It is at this moment that I truly understand how to use them.

Andrea Fraser’s 2005 essay from Artforum “From a Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique” has influenced my thinking about institutions. Fraser, a well-known practitioner of “Institutional Critique” creates a clear map through the thickets of art theory that traps unwary art students and writers with its thorny recursive arguments. In the heights of the Bush Administration (as I gained confidence as a teacher and artist), Fraser’s essay became a torchlight through the brambles. “Representations of the ‘art world’ as wholly distinct from the “real world’ like representations of the ‘institution’ as discrete and separate from ‘us,’ serve specific functions in art discourse.” She continues: “Every time we speak of the ‘institution’ as other than ‘us’ we disavow our role in the creation and perpetuation of its conditions.” Institutions may consider themselves monoliths or giants or people — as corporations are legally considered — but they are not. We make ourselves believe in the power of institutions in a mass mutual hallucination. We are the engines. We are the guts and the life blood.

DinéYahzí’s thesis show of that same era described the “Art Industrial Complex” succinctly. The show included those who are now Indigenous luminaries of contemporary culture, including Raven Chacon and Kaila Farrell-Smith. They started R.I.S.E. an Indigenous artist initiative. Ever since (through museum exhibitions, gallery shows, poetry readings and arts festivals,) DinéYahzí has worked to subvert the dominant power structure of colonial institutions. They redirect honorariums, crowd source grant awards to younger artists and maintain affordable artworks through an Etsy site. It is not easy. Right now BIPOC artists are getting their due, but the hungry giants really want a bit of those artists’ souls, their pound of flesh. The behemoths are not necessarily on anyone’s side. They want assimilation into the corporate body. DinéYahzí keeps from being digested into the giant’s belly by not ever being completely palatable to it.

In 2013, my main beef with institutions was personal. I didn’t want to be an adjunct anymore, contingent. I needed a full-time job and I wanted in on this Art World business. I was trying to gather the sticks in front of my feet looking for enough to make a meager fire. Education, cultural and nonprofit boards and their administrations looked to the gospel of Silicon Valley. Capital and real estate were injected with steroids. Evangelists for atomizing labor used the peculiar fantasy language of management speak. Everyone was “disrupting.” But what was disrupted was labor. Humanity and knowledge were being disrupted.

The angel Clarence tells George Bailey that they don’t use money in heaven. George retorts, “It comes in pretty handy down here, Bub.” I still needed a gig. The primary question (and I think this is everybody’s question) is how do you live a human life within Capitalism without completely losing your life force? It took me awhile to see this wasn’t a “me” problem. The shape of an alternate and more humane institution started to take form, the original impetus for The Ground Beneath Us. I took some of the main ideas from Ringing the Temple Bell and applied them to what I saw as the failure of college level art education. PNCA was readying a move into a swell new building. There was a lot of handwringing about retention, tuition cost, and what students want.

I took advantage of a President’s Initiative to run a pilot of The Ground Beneath Us, which meant to address a number of problems. The program would abandon the 16-week, four class a semester model. Instead, it presented a year-round, three-year curriculum. Students would pay significantly less tuition. This program was designed to accentuate the best of Portland by making a small-scaled, hands-on, nature-based and humane program. It was designed to give space for the student to fail in order to truly learn. Process was the goal, not the closed loop of a finished product. As a first task, students would build their own studio, the space through which students think and learn. In place of a menu of classes, monthly symposia would provide intensive three-day bursts of lectures and discussion with faculty from liberal arts. There would be biweekly intensive two-day workshops with studio faculty to cover specific techniques. I thought about creating a space where new students could learn how to be artists in the direct sense of studio classes, but also studio practice and basic living skills. Faculty would be expected to have studios nearby and they would be paid well. This was not art nervously aping other disciplines. It was asking art to truly be itself. It’s not really revolutionary. I pulled much of this from Black Mountain College, Paolo Friere, Indigenous activists, craft schools. I didn’t have the research then, but I do now. This kind of all-body learning is what all humans need, regardless of the discipline.

The President’s Initiative was an opportunity to create my own program and install a new model within the institution. It was a contentious and resentful process getting the pilot approved through faculty governance. As we crafted the plans, my mother was diagnosed with kidney cancer. In May, The Ground Beneath Us was set to go. My colleague, art historian Joan Handwerg and I hand-picked eight students.

By June my mother had had very invasive surgery. I visited her in New Hampshire in late June. There was some hope that the surgery would extend her life. It was the last time I saw her. She died two weeks later just as the four-week pilot was about to begin. My shock moved into deep mourning. So I barreled ahead. It was a charged, sad and exuberant month. It was a success for our goals, performed on a threadbare shoestring budget. We had evidence. We had documentation. We also had no support from the administration. Their goal was to create a more “professional” school focusing on illustration and graphic design. No matter what we presented it wouldn’t have mattered. It was all about corporate sponsorship.

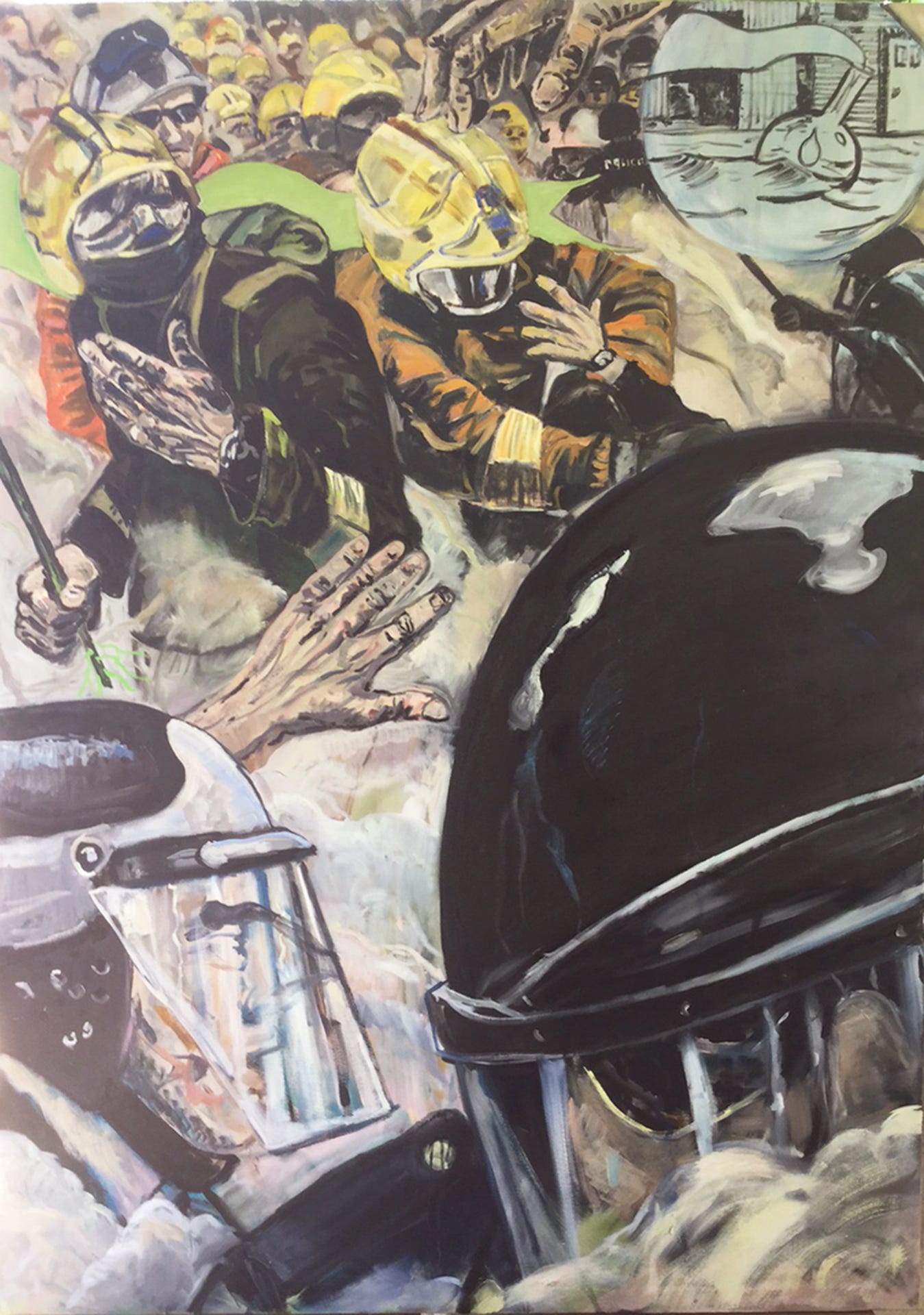

In 2015, I moved to Reed College as a visitor. At first it seemed I found a place that I could easily bring in all that I learned from The Ground Beneath Us. Much of that material made its way into my classes at Reed. But I was still a visitor. The same year that Trump was elected I found out that my appointment was ending. The two events coincided to create panic. It’s one thing to be anti-institutional if there seems to be stability just beyond the horizon. It’s another when the horizon is on fire. My work was filled with images of riots and floods, of a floating crucible: change and hope precariously aloft on the skin of a wave. So when the floodgates of fascism and white supremacy opened in late 2016, anti-institutionalism was something I seemed to share with the Oath Keepers. I had to rethink my stance. Suddenly those institutions were bulwarks against authoritarianism.

It was asking art to truly be itself. It’s not really revolutionary.

In 2017, I partnered with my friend Armand Balboni to revive The Ground Beneath Us as an artist fellowship and residency. It was centered in Waterford, Virginia where Armand and his wife Tracy have a home. This is how we phrased it: “The heart of the program is visual storytelling. The fellowship capitalizes on the centrality of stories to shape understanding. History and ecology braid their way through the soil of the village. The stories that emanate from Waterford are stories of resistance that have resonance for contemporary students and artists. The Quakers who founded and built Waterford offer a model of social justice. The deep history of the place can provide new narrative structures for a younger generation.”

In 2019, The Ground Beneath Us convened with our first fellows Folsom 50 (Tracy Schlapp and Danny Wilson) and painter Arvie Smith. Our mission focused on social justice and ecological histories. It was a scrappy but promising start. I had just won a Guggenheim Fellowship for a body of work based on abolitionist John Brown, whose story I encountered on my first trip to Virginia. For the first time, I felt like I was building the structure of a dream. It wasn’t easy or simple, but I was no longer worried about my lack of an MFA. I wasn’t waiting on academic hiring committees. I was building the institution conceived in that cold October garden at Abrons Art Center.

We had plans for a year-long intensive in Waterford in 2020. I was looking at other possible fellows and I had two solo museum exhibitions scheduled. I had just co-curated an exhibition at Orange County Museum of Art. Then the pandemic hit. Everything closed. We all started pivoting like those floating crucibles caught in an eddy. In the depths of the pandemic and the last fervid year of the Trump presidency, my thinking about institutions evolved. Something was blooming under the dry surface of the trauma.